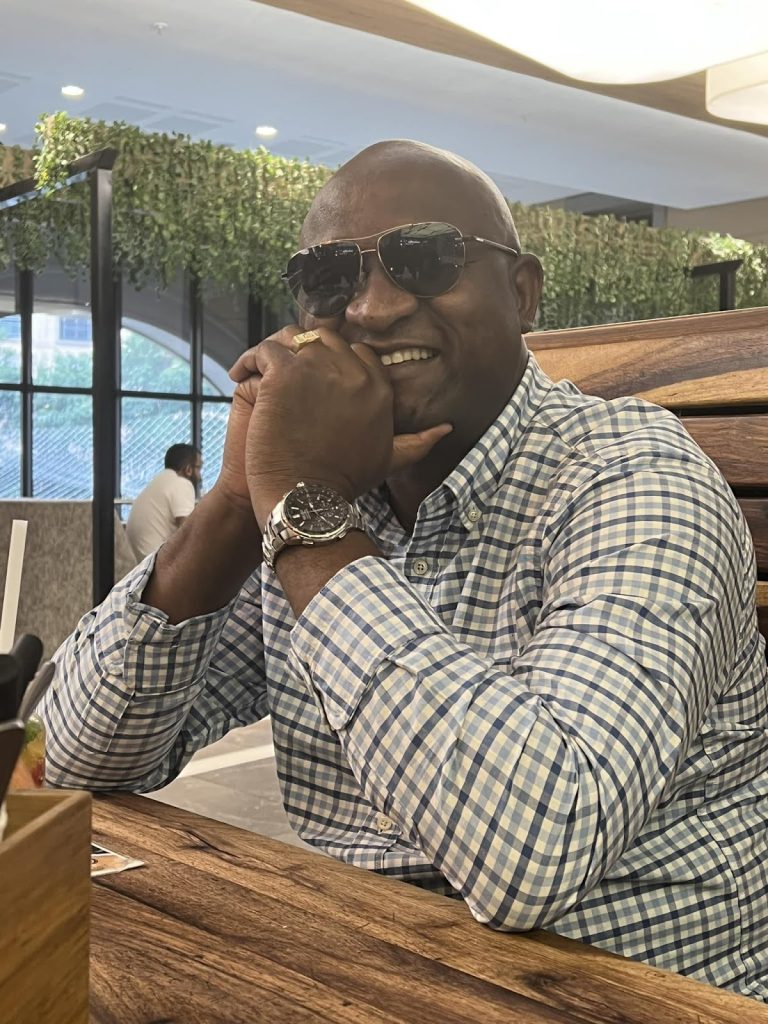

Sophia Foster's life was shattered by a workplace injury, but the real trauma came from the system that was supposed to protect her. For three agonizing years, she's fought for justice, answers, and the basic right to walk again. By JACK McBRAMS It was a little after 4 p.m. on September 6, 2022, when Sophia Foster’s life took a dramatic turn. As the workday was winding down at Alliance One Tobacco, one of the country’s major tobacco companies, a co-worker’s trolley slammed into her knee hard. She stumbled, wincing. It hurt. But she assumed it was just a knock. By sunrise the next day, her leg had ballooned to twice its size. Two years later, Foster, now 37, lives in persistent pain and job insecurity. She is jobless, destitute, and dependent on well-wishers for food and rent. But worse than the physical injury, she says, is the betrayal by a system that was supposed to protect her. Her case opens a troubling window into how some workers in Malawi are abandoned after workplace accidents, bullied into silence, and gaslit into giving up. “They said I was faking. I limp during the day, but I walk fine after work. Even after surgery, they still didn’t believe me,” she says. Foster was employed as a seasonal waiter at the tobacco factory—a physically demanding support role that involved moving trays of processed tobacco, pushing heavy trolleys between workstations, and assisting machine operators to ensure the smooth flow of production across the factory floor. The Day Everything Changed Foster recalls the moment of impact vividly. It wasn’t just the trolley that hit her—it was everything that followed: indifference, bureaucracy, and humiliation. When she first reported the injury to her supervisor, she was told, “We’ll talk tomorrow.” That conversation never happened. Instead, her leg swelled overnight, and her journey into a healthcare maze began. She went to Bwaila Hospital. The X-ray machine was down. Referred to Kamuzu Central Hospital, she was informed that the service would be difficult to access. Back and forth she went, between company clinics and hospitals that didn’t seem to want her. When she finally got an X-ray at Daeyang Luke Hospital in Lilongwe, something was off. Her scan was mislabelled under a different name—“Sophie Master.” The diagnosis stated that there was no fracture, only soft tissue damage. Still, her knee “had shifted” and could “start leaking watery tissue,” the doctor warned. But back at the company, that report was dismissed. “They said tissue tearing isn’t serious. That I should report to work as usual,” she recalls. So Foster did. Every day. With a swollen, painful leg. Because at her workplace, no sick note from the doctor meant sick leave. And absence without authorization could mean being fired. The auction floors at Alliance One Tobacco Gaslit, Mocked, and Misinformed Foster’s efforts to get treatment were met with suspicion and derision. “Some of my workmates mocked me, saying I just wanted compensation. One doctor at the company even took away my walking stick, accusing me of faking my condition,” narrates Foster. When the company’s in-house doctor died, his junior took over—but continued the gaslighting. Foster submitted letters. She made follow-ups. She got no responses. The breaking point came when her health passport from Kamuzu Central Hospital—detailing real prescriptions and a precise diagnosis—was dismissed. She claims that company doctors only took her seriously after other specialists affirmed the injury was legitimate and required urgent care. In March 2023—seven months after the injury—she was finally told not to report for work. But the company still wouldn’t support her medical bills because “it was off-season.” When the newly-hired company doctor was tipped that “a woman is faking an injury,” he too was skeptical about the injury. But assessments showed otherwise. Eventually, the company hired a respected KCH doctor, Dr. Kumbukani Manda, who recommended an MRI scan at Africare. The results were shocking: Foster’s knee ligaments were severely damaged. She required knee arthroplasty (surgery involving metal and pipe insertion). Then came a bizarre twist. The man who had injured her, by pushing the trolley, had reportedly proposed to her romantically before the incident. Foster rejected him before filing a sexual harassment report. The man admitted to Foster’s report, yet the verdict ruled the trolley incident was “an accident.” Neither she nor he received the judgment from the disciplinary panel—both were told separately, raising further suspicions. Surgery in Zambia—And a Final Insult Eventually, Foster got the surgery she needed—but not in Malawi. In Zambia, Foster underwent knee surgery and was advised by doctors to remain hospitalized for 21 days to allow proper healing. But her employer reportedly insisted she return to Malawi just five days after the operation, saying they would handle the rest of her recovery locally. Under pressure, Zambian doctors removed her stitches prematurely—nine days ahead of schedule—and declined to issue a full medical report, offering only a basic physiotherapy schedule instead. “They said they couldn’t trust that Malawian doctors would respect their work,” Foster recalls, her voice low with embarrassment. “They just wanted to cover their tracks.” Back in Malawi, she shared photos of her knee with her employer and explained she was in no condition to resume work. Though the company acknowledged her plea and advised her to begin physiotherapy, it didn’t start until a month later—an unusual delay, she says, compared to the immediate care provided to other injured workers. Foster started physiotherapy a month later. Her physiotherapist recommended a knee press worth K60,000 to help her regain her ability to walk. The company gave her K20,000. When she explained the medical recommendation, she was told to write a letter. She did. To date, she has received no response The Ministry of Labour confirmed to PIJ, Foster's case was reported to their Lilongwe District Labour Office. "Yes, the employer reported formally on a prescribed form," the Ministry’s Spokesperson Nellie Kapatuka told PIK. “Our office called the injured worker... to be referred to the hospital for assessment." Ministry of Labour Spokesperson, Nellie Kapatuka According to Kapatuka, Alliance One Tobacco fulfilled its reporting duty under the Workers’ Compensation Act (WCA) and further explained that the Ministry's role involves the Occupational Safety, Health and Welfare (OSHW) Act of 1997 for accident prevention, and the WCA for compensation when OSHW measures fail. Asked about enforcement actions against Alliance One Tobacco in this case, Kapatuka replied, "Not yet." She noted the Ministry is reforming both the OSHWA and WCA to improve worker protections, with input from employers and employees. The Bigger Picture Sophia Foster’s story is not just about one injured worker. It’s about how Malawian labour laws are failing in practice. It’s about a system that puts profit over people. It’s about how gender, power dynamics, and company loyalty intersect to silence women such as her. It's perhaps the reason the Women Lawyers Association (WLA) has taken up Foster’s case and filed a personal injury claim in court against Alliance One Tobacco next week. “We should have filed earlier, but we had been busy. We will file with the courts next week,” WLA Chief Executive Officer, Golda Rapozo, told PIJ. On the other hand, Alliance One Tobacco insists it has operated within the law. "The health and safety of our employees is a top priority... We provided all the necessary support to Sophie and, where required, continue to do so within the parameters of the law," the company said in a written statement. Foster’s case falls under the Workers’ Compensation Act (WCA) of Malawi—a law designed to ensure that workers injured on the job are compensated for their suffering and loss of income. The WCA mandates that employer report any workplace injury and death of their employees during employment. The Act further allows for the commencement of legal proceedings when the injury is a result of negligence by the employer. Under the Act, employers must report all workplace injuries to the Workers' Compensation Commission within 14 days; injured employees are entitled to free medical care, transport to the hospital, and rehabilitation; and compensation is calculated based on the degree of permanent or temporary incapacity and loss of earnings. In her case, none of these employer obligations seems to have been adequately delivered. There was no medical review board. No independent assessment. No formal compensation process was initiated by Alliance One Tobacco. “They didn’t even file with the Commission,” said a labour lawyer familiar with her case. “That alone is a breach.” The matter will, eventually, play out in court. While Sophia waits—still—on the compensation she was promised, Sophia asks just one thing: “Is it too much to ask that when you get injured at work, they should believe you?” This article was published by the Platform for Investigative Journalism (PIJ). The PIJ is committed to professional and independent journalism. ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

.jpg)

.png)