or Malawians to access fertilizer through the Affordable Input Programme(AIP), financial services and other health services, as well as even getting a passport, a driving licence and a national identity card, they have to surrender some of their unique physical and behavioural characteristics.

This personal data has to be stored through different states apparatus through biometric technology. This is mainly used for identification and access control or for identifying individuals who sometimes are under surveillance.

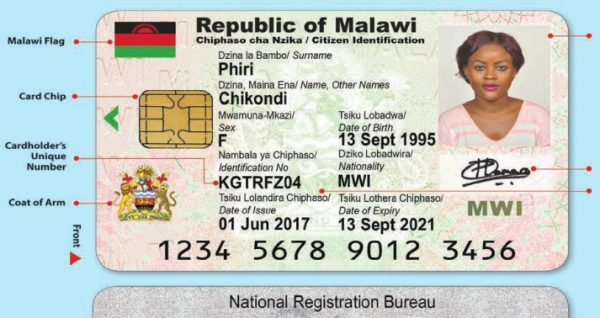

As recent as six years ago, Malawians were devoid of any official national identification system. Despite passing the National Registration Act in 2010, it was only in 2017, that the Malawi Government and its international partners embarked on a multi-faceted program to develop the country’s first national biometric registry and the National Registration and Identification System (NRIS).

Initially, Malawi relied on traditional systems, such as village registers and endorsements from local leaders, as well as the District Commissioner for identification and citizen recognition, methods which left a lot of gaps and paused threats to various systems as far as authentication and security were concerned.

A few Malawians here and there had legal documents that passed for IDs, including passports, driver’s licences and voter cards, not all of which used biometrics. This resulted in the average Malawian getting denied access to particular government services and processes, travel documents, banking facilities, and other services that required confirmation of identity and citizenship.

In April 2017, Malawi’s established its first ever multi-modal biometric citizens’ database, in an exercise aimed at registering all Malawians aged 16 and above in a permanent and continuous system. As of today, more than 9 million citizens are registered with their biometric attributes and issued national identity cards.

In line with the Malawi Government Gazette notice no. 67 of 10th August 2018, the Malawian central bank, The Reserve Bank of Malawi (RBM) issued a directive to financial institutions that the National Identity Card be adopted as the primary identification tool for individuals in the country by 30th September 2019.

The notice by the Malawi Government Gazette endorsed by the then Minister of Finance, Economic Planning and Development, Goodall Gondwe partially stated that pursuant to Section 16 (ii) a. of the Financial Crimes Act, “…the following documents as official or identifying documents for the following customers or class of customers; – (a) Malawian citizens – valid National Identity issued by the National Registration Bureau as a primary form of identification…”

Following this, to comply with the Reserve Bank’s Know Your Customer (KYC) directive, all financial institutions called for verification and recording of the National Identity Document for all customers that are Malawian Nationals, including businesses. Failure to conform risked customers’ accounts being blocked and ultimately closed. The only acceptable ID for this exercise, and any other transaction going forward, became the National ID.

The notice necessitated mobile networks and communication companies to register all SIM cards in Malawi on a central database, whereby a customer’s national identity number is required to be verified and recorded when purchasing or replacing a SIM card.

The Malawi Communications Regulatory Authority (MACRA) enforces KYC in this regard, and the announcement followed an extensive SIM card registration campaign that prompted citizens to register their SIM cards or risk losing their lines of communication.

Despite the exercises meeting hesitancy from other members of the public, today, every customer with a functioning financial or communication service must have submitted their identity information, which comprises biographic and biometric data.

The NRIS is now a single integrated registry, and the Malawi national ID has since become the central form of identification for every system in Malawi that requires identification and authentication.

The NRIS serves as a central reference point which permits the government and other stakeholders, including financial service providers, communication service providers, and social payment schemes to link Malawians’ identities across various databases, a system that admittedly improves the delivery of key services.

It goes without saying that the exercise requires forbearance from citizens to give up their individual private information, which can be profound in nature. It is also incontrovertible that the citizens would anticipate that their data is dealt with, with the utmost care and discretion.

According to Section 8 (2) of the National Registration Act (2010), it is stipulated that the national register shall consist of the following particulars relating to each applicant;- the applicant’s full name; the applicant’s principal place of residence in Malawi; the names of the applicant’s parents; the applicant’s permanent home address (Village, T.A. and District; plot number, township and local authority); the applicant’s sex; the applicant’s date of birth; the applicant’s place of birth; the applicant’s marital status; the date of registration of the applicant and the registration number; in case of an applicant who is not a citizen of Malawi, his nationality; height; colour of eyes; fingerprints; photograph; passport number, if any; special observations, if any; and such other particulars as the Minister may prescribe.

Even though the National Registration Act (2010) offers a prerequisite for disclosure of personal data in the national registry, the country has no legal provisions that are specific to biometric data protection.

The available legislation that attempts to address issues of personal data, like the Electronic Transactions and Cyber Security Act (2016), still leaves enormous gaps and tends to be poorly adaptable in dealing with biographical and biometric data that is available to the government and other stakeholders.

The 44th section of the National Registration Act (2010) provides for secrecy, stating that “… no person shall disclose to any other personal information recorded in any register, document, or proof of registration, except for purposes of this Act or any judicial proceedings or the performance of his functions in terms of any law, and no person to whom any such information has to his knowledge been disclosed in contravention of this section shall disclose such information to any other person.”

The same section that provides for secrecy also grants the Minister the authority to furnish any information in relation to any person whose name or particulars are registered under the Act to any Ministry, local authority or body established by or under any law for any purpose of that Ministry, local authority or body.

While having this legislation on record, there are still concerns about biometric surveillance taking place in Malawi unabated at different levels, where if you miss it at one point, you will definitely be caught in its web at one point or the other.

The increased cases of Cyber-Crime related offences show a lack of systemic prevention of access to systems and resources of unauthorized characters to access personal data through exfiltration of protected data, without raising alerts and alarms when access attempts are made by unauthorized personnel or programs.

Cyber-crime perpetrators have been known to scam people, by sending text messages and even calling, with fraudulent allegations that put people in a position to lose money. Usually, the offenders will sound to have enough of the targeted victim’s information, and this has raised questions on where and how they access such classified information. The registration of SIM cards was among others intended as a measure to curb fraud and other related cyber-crimes, and yet the initiative seems to be yielding minimal outcomes in that regard.

The Malawi Police has initially admitted that it is struggling to fight cases of Cyber-Crime related offences, which have been on the increase. In the interim, Malawi Communications Regulatory Authority (MACRA) has initiated a task force on mobile fraud comprised of Police, Prison, Mobile service providers, National Registration Bureau, and the Reserve Bank of Malawi among others, that are jointly looking into ways of combating these offences.

In July this year, during an interaction between the authority and the media in Mzuzu, MACRA Deputy Director of Consumer Affairs, Kelious Mlenga disclosed the authority’s intention to acquire equipment that will be used to detect gadgets that are used in committing crimes.

He elucidated that, tracking offenders by tracing the national identity information attached to the phone numbers used to commit the crime, usually does not lead to catching the real culprits because they tend to use borrowed or bought identification for the acquisition of their SIM cards.

Immigration

The Department of Immigration and Citizenship Services (DICS) under the Ministry of Homeland Security is mandated to provide services to the public in areas of border control, issuance of travel documents, residential and work permits, Visas and Citizenship to eligible persons.

Malawi Government awarded Techno Brain a contract in 2019 to create new passport infrastructure, develop capacity, train DICS staff and supply consumables and finished biometric passports.

In mid-December 2021, Malawi’s then Minister of Homeland Security, Richard Chimwendo Banda, cancelled Techno Brain’s biometric passport system management and production contract with the Department for Immigration and Citizenship Services (DICS) reportedly due to corruption, which Techno Brain denies and is pursuing legal action against the authorities.

Biometric technologies have become a vital part of migration management.

The Malawi Government through the Department of Immigration and Citizenship Services announced that from December 30, 2019, it was introducing an electronic passport (e-passport) that would replace Machine Readable Passport.

The department announced that the purpose of the e-passport was to enhance the security features of the Malawi Passport while at the same time conforming with international standards set by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a specialized agency of the United Nations that regulates civil aviation across the globe.

Since then, Malawi has had an electronic passport, which is a passport booklet embedded with an electronic chip able to electronically store the holder’s details including biometrics. The Malawi electronic passport improved security features derived from a review of the features adopted globally.

Use of Biometrics in Other Civic and Security Functions

Other than identification, the Malawi national identity system and the biometrics attached to it assist the government in enhancing service delivery such as access to financial services, free health services; disaster management and response social support services that include subsidized fertilizer. All these are also now linked with the national identity system to ensure the effective targeting of social safety net programs.

Linkages that have been established between the national identity card and other civic functions, for example, the voter registration system, have ultimately enhanced the quality of service delivery, and even helped lower costs of operations.

The 2019 tripartite election was the first to use biometric registration of the National Registration Bureau (NRB). The national identity card became the only permissible ID for voter registration, and prospective voters were mandated to get registered with NRB, so they could register.

Temporary NRB registration spots were placed in designated Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC) registration centres to ease the burden of aspiring voters acquiring the national ID.

The newly adopted system proved not only convenient to the electoral body by curbing challenges that have been faced in the past like misspelt names, multiple registrations and misplaced photos among others, but also to the voter citizens, whereby it took as little as one minute for a person to complete the registration process, as compared to the past, where registering one voter could take up to 15 minutes.

The voter registration period influenced a remarkable increase in national registry uptake, as citizens continued realizing the multifunctional nature of the national identity card.

The use of biometrics in voting however did not stop others from attempting to commit electoral fraud. Some days into the voter registration process, it was established that posing as adults, minors were registering with the NRB in order to qualify for voting. While the conduct was met with immense backlash and eventually addressed, it is conceivable that a good number of committers got away with the malpractice, and are out there operating with data that is barely factual.

Among other particulars that the national register requires from applicants includes names of the applicant’s parents, which could be used to verify a dubious applicant’s facts, as parents are also required to list names and dates of birth of their children.

Although still subtle and not widespread, the use of biometrics in the Malawian healthcare system is budding. The use of biometrics in patient identification within the healthcare system guarantees various potential advantages that would improve quality health services delivery, including efficient record keeping, reduced medical errors and reduced risk of fraud. The national identity system would warrant the effective recording of vaccines to combat the smuggling of medicines to neighbouring countries.

The national registry uptake among citizens also escalated, with the national identity card as the principal requirement for accessing affordable farm inputs. The Affordable Input Program (AIP) was put in place to attain food security at household and national levels and reduce poverty through increased access to improved farm inputs. The program targets Malawian smallholder farmers that are resource-poor across the country.

The adoption of biometric data ascribed to national IDs in authenticating beneficiaries had apparent benefits of mitigating fraud, whereby in the past the system could be flooded with ghost beneficiaries among others.

It would be typical anticipation that with every beneficiary farmer required to have a valid national identity card, issues to do with fraud would be totally addressed. However, even with the national ID prerequisite in place, the AIP has been mulled with allegations of one person using multiple cards to access the farm inputs. Usually, the person would not be the genuine possessor of even one of the cards, and one would wonder if authentication of beneficiaries using national IDs is even taken seriously. While several perpetrators have been caught in the act, it is apparent that many others have successfully executed the sham.

Earlier this year, police in Dedza arrested two people for possessing 190 national identity cards believed to have been stolen from the Dedza NRB office. The two, an NRB data clerk and a Group Village Headman, got arrested following a complaint by one of the beneficiaries who, when he went to buy fertilizer at one designated depot in the district, found that another person was using his particulars to purchase fertilizer for himself.

This is just one of the many incidents, whereby either NRB officers connive with local leaders to steal people’s identity information, or the beneficiaries themselves sell their national identity cards upon being coaxed by the fraudsters.

When the Ministry of Health rolled out the Covid-19 vaccination, among other requirements to access the vaccination was the national identity card. The Centre for Human Rights and Rehabilitation (CHRR) called for the immediate abolition of the mandatory requirement of the national identity card for Malawians to access Covid-19 vaccines, claiming the practice to be discriminatory and a gross violation of human and people’s rights.

According to CHRR Executive Director Michael Kaiyatsa, access to health services, including Covid-19 vaccines, is a basic human right that should not be conditioned to possession and production of a national ID.

The District Environmental Health Officer for Blantyre District Health Office (DHO), Penjani Chunda however rationalized that the use of national ID in the administration of Covid-19 vaccines, though encouraged, is not compulsory. He says that the national ID is recorded as part of the parameters, and is crucial to tracing records in the event that someone loses their vaccination card.

Chunda added that because Covid-19 certificates do not comprise biometric data including a facial photograph, linking the certificate to the national ID is one sure way of accessing one’s biometric data for the purposes of authentication.

Countries and agencies providing refugee intervention programs are adopting biometric database systems. In January 2014, the UNHCR complete the initial testing of a new biometric system aimed at enhancing registration management and identification verification at the Dzaleka refugee camp in Malawi.

For refugees without any formal identification documents, which counts for most of them, the biometric attributes recorded in the database would become a vital record. UNHCR Director, Steven Corliss, commented that improving the accuracy of data is a priority for the agency, and crucial to their services delivery.

He added that accurate recording of data is also of great significance to the host country, and the experience in Malawi was going to inform their decision on further development and operations around the world in regard to adoption of biometrics.

In pursuit of better business and job prospects, hundreds of refugees have moved and integrated into the local society. Despite government’s efforts and orders of refugee relocation to designated camps, a fair share of them has remained in the society, with others having married, and established stable businesses in the society.

Reports have been there of some refugees conniving with members of the society to utilize their national identity cards in accessing social services that require production of IDs, a development further proving laxity in the authentication of biometric data.

The Principal Secretary of the NRB, Mphatso Sambo, enlightened that apart from the linkages of the bureau with particular financial, civic and social services, the bureau also allows ordinary citizens to seek identity proof information from the bureau.

Upon request for information of any citizen registered in the system for verification and authentication purposes, one should be provided with particulars on the same.

Various institutions can also access biographical and biometric information of registered citizens on demand. Institutions can also arrange with the bureau to integrate with the registry systems, enabling direct access to information, which Sambo remarked that while not mandatory, institutions are highly recommended to integrate with the bureau as it is one way of realizing efficient service delivery.

Implications?

In spite of existing legislation and prerequisites prohibiting the use of biometric data for invalidated purposes, it is not farfetched to believe that the provisions have been routinely ignored and uncontrolled. While aiming at offering a sense of security and belonging, if tactlessly executed, the use of national IDs at different levels can generate undesirable results.

The leniency also establishes a slippery slope of surveillance and monitoring of citizens without defensible intents.

The somewhat relaxed flow of biometric data from the central registry to miscellaneous points, whether on-demand or through direct linkages without structured, feasible safeguarding measures, exposes citizens’ data to ultimate maliciousness.

The probable use of citizens’ IDs by unauthorized individuals or groupings, demonstrates grave authentication loopholes within the systems of social service providers and other institutions. Some citizens still do not understand the implication of sharing, borrowing, or selling their IDs, which would result in falsified arrests and being denied their rightful social services and benefits.

The NRB, as the core of the citizen registry, ought to intensify conditions on data access, as well as direct linkage to the central registry. Enhanced civic education on the implications of sharing and selling national identity cards, which perceptibly hold their biological and biometric information, is also paramount.

On this, the Principal Secretary of NRB remarked that the bureau prioritizes public relations service and civic education. He said that as a cross-cutting agency, while maintaining good relationships with other agencies and departments, they work with the Ministry of Civic Education and National Unity, the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology in conveying civic education.

For effective interface and associations, the bureau works with the Ministry of Local Government where there are local leaders, district commissioners, councils, and district political leaders, all of which are actively involved.

He emphasized that having offices in every district of the country and other outreach posts in several post offices of the country, helps the bureau fluently conduct outreach services on public relations issues.

Personal Data Collection without Protection

Malawi has acknowledged that increased digitalisation, personal data collection, processing, and storage by public and private sector institutions have risen tremendously and despite weaknesses in the way people are abusing the ID documentation, it still, therefore, warrants greater protection through a dedicated law.

Government of Malawi issued a call for public comments on the Data Protection and Privacy Bill, 2021, and the Presidential Delivery Unit also organized the Digitalization Labs from 25th April – 10th May 2022 which resulted in the Malawi ICT and Digitalization Policy Roadmap 2022-2026.

The roadmap identifies Cybersecurity, Data Protection & Regulation as a priority area as it observes that lack of comprehensiveness in data protection and inadequate frameworks impede digitalization therefore government has developed bills in the pipeline to set up bodies and laws for enhanced data protection and security.

The proposed drafted Data Protection Bill seeks to deal with issues of Personal data protection, fair processing of personal data and consent.

The Constitution of the Republic of Malawi protects privacy under Section 21 says, “every person shall have the right to personal privacy, which shall include the right to be subjected to – (a) searches of their person, home, or property; (b) the seizure of private possessions (c) interference with private communications, including mail and all forms of telecommunications.”

“Yet,” observes Jimmy Kainja, a lecturer in media, communication and cultural studies at the University of Malawi, “it is worth noting that Malawi also lacks a data protection law, particularly for the digital age, which is critical in ensuring safety and protection online.”

Kainja agrees that since its implementation in 2018, the national ID has become the only form of identification for all public transactions, including voter registration, mandatory SIM Card registration, banking, MRA, farming subsidies, cash transfers, and Covid-19 vaccinations.

“Implementing the national ID means people’s data is centralised through the ID system,” he says in his write-up in the Southern Africa Digital Rights Issue Number 1: Data and Online Privacy Under Attack.

—This article on digital surveillance was supported by the Media Policy & Democracy Project, jointly run by the University of Johannesburg and the University of South Africa.